Syed Huzaifah Ali Nadwi

Cambridge, UK

My students and a few close friends here in the West, many of whom do not speak Urdu but saw this dialogue being discussed online and in the wider media, asked me to write a brief, accessible summary of what actually took place and why it matters. A number of them come from secular university and professional environments, where Islam is often encountered through headlines, stereotypes, or polarised debates rather than through real conversation, so their questions were sincere and practical: what was said, what was the atmosphere, and how should we as Muslims read it without turning it into a spectacle. As a fellow Nadwi, I also felt it would be unfair to stay silent when people are trying to make sense of it, so I’m putting down these reflections with sincerity, without claiming any credit for the effort Mufti Shamail Nadwi himself put forward.

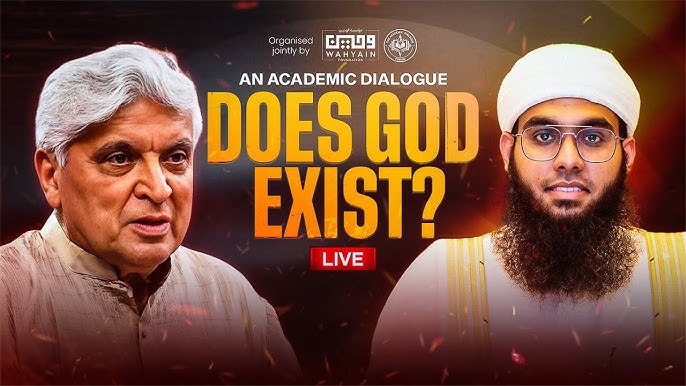

This was a public dialogue between Mufti Shamail Nadwi and Javed Akhtar, centred on the biggest questions that sit underneath almost every modern conversation about Islam: Does God exist, what is the purpose of life, why is there suffering and evil, and whether religion (and Islam in particular) can still speak to the modern mind with credibility and compassion. For many viewers, the “headline” was simply this: a traditionally trained scholar entering a mainstream space to engage an articulate, culturally influential sceptic, in front of an audience that was never going to automatically side with faith.

To make sense of what was happening for someone who does not live in the Urdu-Hindi world, it helps to name the atmosphere as much as the arguments. Javed Akhtar is not merely “a man with opinions”. He is a cultural institution: a celebrated lyricist, screenwriter, and public intellectual figure in the Indian mainstream, widely associated with a confident, polished scepticism towards religion. In the imagination of many Urdu-speaking Muslims, he has long represented a certain kind of educated atheism, not hesitant, not embarrassed, but socially protected, witty, and settled. So when word spread that a madrasa-trained scholar would share a stage with him, the moment carried a weight beyond the usual curiosity of a debate. It raised the question, quietly but sharply, of whether religious speech can enter that room and remain credible, composed, and genuinely human, without being reduced to caricature.

It is also worth noting where this conversation took place and who stood behind it. It was broadcasted by The Lallantop, one of India’s most influential media platforms, and moderated by Saurabh Dwivedi, a widely respected journalist whose long-form interviews are known for drawing large, mainstream audiences across ideological lines. That alone elevated the moment—it meant this was never an “internet-only debate” within a Muslim bubble, but a public dialogue placed in a national media space watched by a broad, mixed audience, including many non-Muslims encountering a traditionally trained scholar in this kind of setting for perhaps the first time. In a climate where Muslims in India often feel that public space is tense, polarised, and unforgiving, that background makes the event doubly significant: the stakes were social as much as intellectual. And the reach reflects it—the flagship upload on The Lallantop’s YouTube channel has already crossed 4.6 million views (as of 22 December 2025), while Mufti Shamail Nadwi’s official channel stands at nearly 6 million. Taken together, the conversation has comfortably exceeded ten million views across platforms, and the numbers are still rising as people continue to discover and share it.

Mufti Shamail Nadwi represents a different kind of authority. A “Mufti” is not simply a preacher or a motivational speaker; in the Muslim tradition, a Mufti is trained in the disciplines that allow a person to answer questions responsibly, to speak with legal and ethical awareness, to weigh evidence, to understand human circumstances, and to communicate the religion with seriousness. That weight matters, because when a Mufti enters a public setting, he is not only representing himself, he is representing a way of knowing, a tradition of learning, and a moral posture.

So this was not entertainment, and it should never be treated as entertainment. It was a public attempt, imperfect like all human efforts, to place faith and scepticism in one room and ask the questions that sit underneath modern life.

To be honest, I felt a genuine sense of relief watching Mufti Shamail Nadwi on stage. Not because I went in expecting a perfect performance, but because the very act of stepping forward matters right now. Public platforms are unforgiving, especially when the subject is God, faith, and religion, and the room is full of people who are not there to give you the benefit of the doubt. For a young scholar to take that risk, and to do so with visible seriousness, quick presence of mind, and a largely dignified tone, is something we should acknowledge properly. Sometimes we forget that the first victory is simply refusing to hide.

And we should say it clearly: taking on someone like Javed Akhtar is not a light thing. He is not just a famous name, he is a symbol. In the Urdu cultural imagination, and especially the Bollywood sphere, he represents a certain confident, polished atheism that many Muslims feel they have heard for years without a robust reply. So the significance of this was never only about one man versus another. It was about whether a madrasa-trained scholar can enter that kind of space and still sound grounded, credible, and human. In that sense alone, the evening felt like a meaningful step.

On a personal note, I felt it even more closely because I know Mufti Shamail Nadwi from the Nadwa environment. He was junior to me when I was studying there and I was the mu’adhdhin, and I would lead some prayers as well, so in that role you end up meeting people informally, exchanging small conversations. So when I say it was reassuring to see him composed on a public stage, I am not speaking about an abstract “speaker”, but someone I have seen as a sincere student of knowledge in real life.

That personal detail changes the way a person watches. When you have seen someone in the rhythm of ordinary days, in corridors, routines, and the quiet seriousness of a learning environment, you do not only evaluate their words as if they are a talking head on a screen. You feel the weight of what it takes for a student of knowledge to walk into a room where many people are not neutral towards faith. It is not only an intellectual task; it is emotional and spiritual too.

From a wider madrasa angle, it felt emotionally loaded as well. Our madrasas have been pulled into too many headlines for the wrong reasons, and too much of the public “image” is shaped by short clips and shallow controversy. In that climate, watching a Nadwi voice represent Islam in a composed and articulate way, without collapsing into either aggression or apology, felt like something to be grateful for. Even if someone has critiques, the wider impression was still positive: a scholar who can engage, not just preach.

I also found myself appreciating the overall frame of the event. It did not turn into the kind of subcontinental “munazirah culture” many of us have grown tired of, where the audience is basically watching a shouting match and choosing a winner like it is sport. Despite moments of intensity, it stayed closer to conversation than chaos. The fact that respect did not completely break down, and that the discussion remained watchable for ordinary people, is not a small achievement in today’s climate.

What the debate was really about, beneath the surface

Even if a viewer does not understand Urdu, the shape of the discussion is familiar to anyone who has listened to modern scepticism. It circles the questions that keep resurfacing in our age: if God exists, why can we not “see” Him; if God is good, why does evil exist; if religion claims truth, why are there so many religions; if humans have reason, why do we need revelation; if suffering is real, how can faith speak about it without sounding detached.

And for Muslims specifically, the pressure is often this: can we explain belief without sounding defensive, and can we speak about pain without sounding cold?

A meaningful exchange is not one where someone “scores points” and the other side goes silent. A meaningful exchange is one where the audience is made to take the question seriously again. That is why one of the most important outcomes was not a single line here or there, but the wider message that Islam is not a truth that can only survive inside the masjid. A traditionally trained scholar sat on a public stage and spoke as if faith belongs in the public square as well.

One point I kept returning to, after watching the full exchange and also reading neutral reactions, is that Javed Akhtar did not seem to be operating in his usual comfortable, dominant mode. That observation came up repeatedly, and it is worth taking seriously. He is experienced, sharp, and media-savvy. If he still felt slightly restrained, that is not nothing. It suggests that the conversation did shift the room. It suggests that religious speech, when delivered with confidence and clarity, can interrupt the default flow of mockery that often frames public conversations about Islam.

The importance of tone, not because we are weak, but because we are doing da’wah

Because the aim here should be da’wah, we have to be careful with how we speak, even when we are “reviewing” a debate.

I want this to be written in a way that if Javed Akhtar read it, he would not feel abused or mocked. Not because we dilute truth, but because truth carries more weight when it is delivered with dignity.

This is why I am not writing this as a victory parade, and I am not writing it as a takedown. A public dialogue is not a boxing match. It is an attempt to place questions on the table and allow the audience to think. If we turn it into tribal celebration, we may excite our own side, but quietly close the door on the people we were meant to reach.

At the same time, honest reflection is not disrespect. In fact, sincere reflection is part of caring about the work. Public communication is a craft, and any craft improves with refinement.

Language and register

Language is another subtle point, and here I actually think Mufti Shamail Nadwi’s use of English was a strength. It signalled that a scholar is not confined to one register, and that he is comfortable addressing the educated, bilingual listener as well. In a room where many people silently measure “competence” through articulation and language-range, that matters.

The hardest question: suffering, evil, and Gaza

Then we arrive at the heaviest question of all: suffering and the problem of evil.

When people mention oppression, children dying, and injustice, they are rarely asking for a technical answer alone. They are asking, in human language, “Where is God in all of this, and what do I do with the anger in my chest?”

So how do we answer in a way that remains true and also humane?

The Islamic tradition does not pretend suffering is an illusion. It takes suffering seriously. The Qur’an does not speak like a detached philosopher; it speaks like revelation addressing human beings who bleed, fear, lose, grieve, and still have to decide whether they will bow or rebel. The answer it gives is not a single slogan. It is a worldview.

In that worldview, evil is not one category. Some evil is human cruelty, chosen by humans, not forced by God. If someone commits oppression, the moral weight of that oppression belongs to the oppressor. Human freedom is meaningful, and freedom includes the possibility of wrongdoing; a world where no one can choose wrong is not a world with moral responsibility.

At the same time, Islam insists that life is not the whole story. If death is the end, then suffering has no meaning, and injustice has no final court. But if resurrection is real, then suffering is not ignored; it is accounted for, compensated for, and judged. The Hereafter is where the moral balance is completed.

Many people demand that the full judgement must happen here, in the short theatre of this life. Islam teaches that the full judgement happens when the curtains close, not while the play is still running.

None of this trivialises pain. It places pain inside a horizon large enough to hold it, so that pain does not become an argument against meaning itself.

And this is where Gaza enters the discussion in a way that is deeply uncomfortable for a certain kind of modern scepticism.

Because Gaza is not only a political headline. It is also a spiritual mirror.

At the same time, Gaza also exposes something else that many sceptics do not know how to process: the way faith can intensify under pressure. Anyone who has watched even a few of those raw clips circulating online has seen it, whatever their politics. People with almost nothing left still saying “Alhamdulillah”, still praying, still clinging to Allah, still speaking about the Hereafter with a calmness that does not look manufactured.

In that sense, it is hard not to feel that the people of Gaza are among the most striking examples of believers in our time, not because suffering automatically makes someone righteous, but because we are literally watching īmān increase under fire. You see people who have lost homes and family still speaking about Allah with a stability that many of us struggle to hold in comfort.

This does not solve the problem of evil in one sentence, but it does challenge a simplistic claim: that hardship inevitably crushes belief. Sometimes, by Allah’s permission, it purifies it. It makes īmān burn brighter, not dimmer.

If someone wants to be intellectually honest, they have to explain that too, not only “Why suffering?”, but also “Why this kind of faith in the middle of suffering?” Because that kind of faith is not produced by argument alone. It is produced by a relationship with Allah.

The craft of public engagement

This is what keeps returning to my mind: this is not a field that everyone can casually walk into. People sometimes assume that sincerity and knowledge are enough. They are essential, but the craft of public communication is also real.

Media training matters. Pacing matters. Framing matters. The ability to keep warmth while disagreeing matters. The ability to speak to the audience, not only to the opponent, matters. These are not cosmetic skills. They are part of da’wah now, because the public square is where many people meet Islam for the first time.

There is a useful litmus test I have heard from Shaykh Abdel Hakim Murad in a different context, but it applies here perfectly.

Imagine an ordinary non-Muslim widow in a small village, someone who has only ever heard of Islam through television. She has heard Islam through headlines, through fear, through stereotypes, through the worst kind of soundbites. She is not reading Arabic. She is not reading philosophy. She is simply listening.

What do we want her to feel: confused, pushed away by tone, and left thinking religion is either harsh or irrational, or quietly reassured that faith is not afraid of questions, and that belief can be both intelligent and humane? Holding that imagined listener in mind changes everything. It forces clarity. It forces gentleness. It forces you to remember that you are not performing for your supporters.

Intention: the thing that can save or ruin the whole effort

I also want to say something very clearly, because it is the spiritual core of how Muslims should view events like this. We should keep our intentions in check, not only before debates, but before every action, and especially before public engagements like this.

A person can “defend Islam” and still ruin the reward by seeking ego.

A person can “win arguments” and still lose adab. A person can “humiliate the other side” and still fail in da’wah.

So the question is not merely, “Did we answer?” The deeper question is, “How did we answer, and why did we answer?” If the intention is da’wah, then our aim is not to crush a human being. It is to remove barriers that sit between a human being and his Creator.

Du‘a for Javed Akhtar, not celebration of defeat

This is why I cannot end without saying: whatever we think of Javed Akhtar’s views, we should not forget him in duʿāʾ.

He represents a certain kind of atheistic confidence for many people, and that itself is a reason to feel the weight of the task, not to celebrate his humiliation. If the intention of engagement is da’wah, then it makes sense that we quietly pray for guidance for him and for those like him.

The point is not to “defeat” a person. The point is to open a door.

The closing moment that mattered more than the heat

That is why the closing moment felt unexpectedly refreshing. When Javed Akhtar said, in effect, that he and the Mufti would now go and eat together, it was a small line, but it carried a big message.

It reminded us that disagreement can remain principled without becoming vicious, and that dialogue does not have to end in bitterness. In an age where people are trained to hate each other for clout, that one moment was its own quiet da’wah.

A Qur’anic reminder for “tomorrow”

And if I could end with one sincere reminder, it would be this.

Allah says:

أَفَحَسِبْتُمْ أَنَّمَا خَلَقْنَاكُمْ عَبَثًا وَأَنَّكُمْ إِلَيْنَا لَا تُرْجَعُونَ

“Did you think We created you without purpose, and that you would not be returned to Us?” (Sūrat al-Mu’minūn 23:115)

And Allah says:

يَا أَيُّهَا الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا اتَّقُوا اللَّهَ وَلْتَنظُرْ نَفْسٌ مَّا قَدَّمَتْ لِغَدٍ

“O you who believe, be mindful of Allah, and let every soul look to what it has sent forward for tomorrow.” (Sūrat al-Hashr 59:18)

These are not verses for Muslims only. They are questions placed before the human being.

And here I want to speak with sincerity, not as a polemic, and not as a performance. Javed Akhtar is reaching an age where the question of “tomorrow” becomes sharper, not softer. None of us knows when death can come. And sometimes the hardest barrier to faith is not evidence, but social pressure and personal history: “I have spent my life saying this. How can I now return?” But returning to Allah is not humiliation. It is courage.

Not every atheist arrives at atheism through atheistic arguments. In fact, for many people, the “argument” is often the last layer, not the first. What really shapes their distance from God can be culture, environment, trauma, disappointment, hypocrisy they witnessed in the name of religion, a deep sense of injustice, or simply the desire to belong to a particular social world where faith is treated as unsophisticated. Sometimes it is not that a person has examined every proof and reached a final conclusion, but that life has formed a posture in the heart long before the mind began to debate. That is why da’wah cannot be reduced to logic alone. We need clarity, yes, but we also need mercy, patience, and the emotional intelligence to recognise that the path back to Allah is often blocked by experiences and fears as much as by syllogisms.

If Javed Akhtar ever feels even a flicker of doubt about atheism, then he should know: guidance does not require theatre. A person can accept truth privately. Of course, entering Islam begins with the shahādah, sincerely affirmed with the tongue and believed in the heart. He does not need to announce it to the world, or perform it for cameras. He only needs to be truthful with his Creator.

Debates will come and go, clips will trend and vanish, and audiences will move on to the next spectacle. But the soul will not move on from its meeting with Allah. That is the real “tomorrow”.

One final reflection I did not want to leave unsaid. What makes this moment even more thought-provoking is that Javed Akhtar himself is not coming from a cultural vacuum, nor from a background untouched by learning. By family history, he comes from a line associated with Urdu scholarship and intellectual seriousness, and it is widely noted that his forebear Allāmah Fazl-e-Haq Khairabadi (d.1861) was a major scholar and also remembered as a freedom-era figure who suffered exile for his stance in 1857. That should keep us humble. Because it reminds us that disbelief is not always born from “arguments” alone, and faith is not guaranteed by bloodline, reputation, or even a scholarly heritage. And it reminds us of something even deeper: we cannot take our own offspring for granted either. The Qur’an frames that fear with a tenderness that Shaykh Abul Ḥasan ʿAlī Nadwī would often quote, especially when speaking about the end of life and the only question that truly matters. Allah says:

أَمْ كُنتُمْ شُهَدَاءَ إِذْ حَضَرَ يَعْقُوبَ الْمَوْتُ إِذْ قَالَ لِبَنِيهِ مَا تَعْبُدُونَ مِنْ بَعْدِيۖ قَالُوا نَعْبُدُ إِلَٰهَكَ وَإِلَٰهَ آبَائِكَ إِبْرَاهِيمَ وَإِسْمَاعِيلَ وَإِسْحَاقَ إِلَٰهًا وَاحِدًا وَنَحْنُ لَهُ مُسْلِمُونَ

“Were you present when death came to Yaʿqūb, when he said to his sons, ‘What will you worship after me?’ They said, ‘We will worship your God and the God of your fathers Ibrāhīm, Ismāʿīl, and Isḥāq, one God, and to Him we submit.’” (2:133)

Even a Prophet’s concern at the edge of death was not legacy or status, but one question: will my children remain anchored to īmān? So if this dialogue did nothing else, it should at least push all of us to make duʿāʾ for guidance, to guard our own hearts from arrogance, and to stop assuming that “good lineage” or “good upbringing” automatically equals a safe ending.

Overall, I still see this public dialogue as a good step in the right direction. I would rather we learn to do this well, repeatedly, than retreat into silence and then complain that public discourse is dominated by voices that misrepresent faith.

Mufti Shamail Nadwi deserves credit for stepping forward in a difficult climate. And if the right lessons are taken, the next time will not just be a good showing, it could become a truly powerful act of da’wah for the people this was always meant to reach.

May Allah purify intentions, grant wisdom in speech, place barakah in sincere efforts, guide those who are searching, soften hearts that have hardened, and make our words a means of opening doors rather than closing them.

Aameen

May Allah subhanautala Guide all of us and especially Javed Akhtar sab to accept the truth about existence of God.

Pray for Javed sab. Ameen Eman pe khatma bil khair ata firmaye.. otherwise he will be in Big Loss

Āmīn. May Allah guide him to the truth and grant him a good ending, and keep all of us firm on īmān. JazakAllah khayr for the reminder.

I read all the articles and I liked them. Since there are no subtitles for the video in English or Arabic, at least it summarized what the debate was about. Thank you for these efforts.

Jazakumullah

📺 English-subtitled video of the full debate:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DM4pkpv7Yhw&t=1s