Syed Huzaifah Ali Nadwi

Cambridge, UK

It has been over a year since my beloved father, Maulānā Syed Naeem Akhtar Nadwī (RA), returned to his Creator. Over the past year, many people had asked me, again and again, to write something about him, as if writing might steady the heart, or at least give grief a place to sit. I had tried more than once. Every attempt had ended in the same way: I would begin, I would look at the page, I would hold the pen, and I could not move forward.

Part of that hesitation was fear, not only of grief, but of injustice. A life like his cannot be summed up in a small piece without leaving so much unsaid, and I felt that writing too quickly would reduce him to a few paragraphs, as though that could ever do him justice. That is also why the work we are now doing, which I will return to towards the end of this article, matters so much: to gather what his students and those who truly knew him carry of his knowledge, his adab, and his quiet influence, and to preserve it with the care it deserves.

The strangest part is that I have written so much in this past year, and yet, when it comes to him, the words refuse to line up the way they do for anything else. I have managed to write about other things, and even to write for others, composing eulogies and reflections in Arabic, Urdu, and English. But when it comes to my father, it is different. It demands a restraint and reverence that I still struggle to bring to the page. The pen behaves as though it has forgotten its duty. Since his passing, it has felt as though the pen simply does not work.

And when he passed away, and I returned home, these lines came out of me without even thinking. They were my own words, but in that moment they did not feel like “writing”; they felt like speech pulled straight from the wound.

جو شمعِ کارواں تھے کل، وہی محفل سے رخصت ہیں

فضا مغموم سی ہے اور، دلوں پہ غم کی شدت ہے

“The one who was yesterday the caravan’s guiding lamp has now departed the gathering;

the air feels soaked in sorrow, and grief presses heavily upon hearts.”

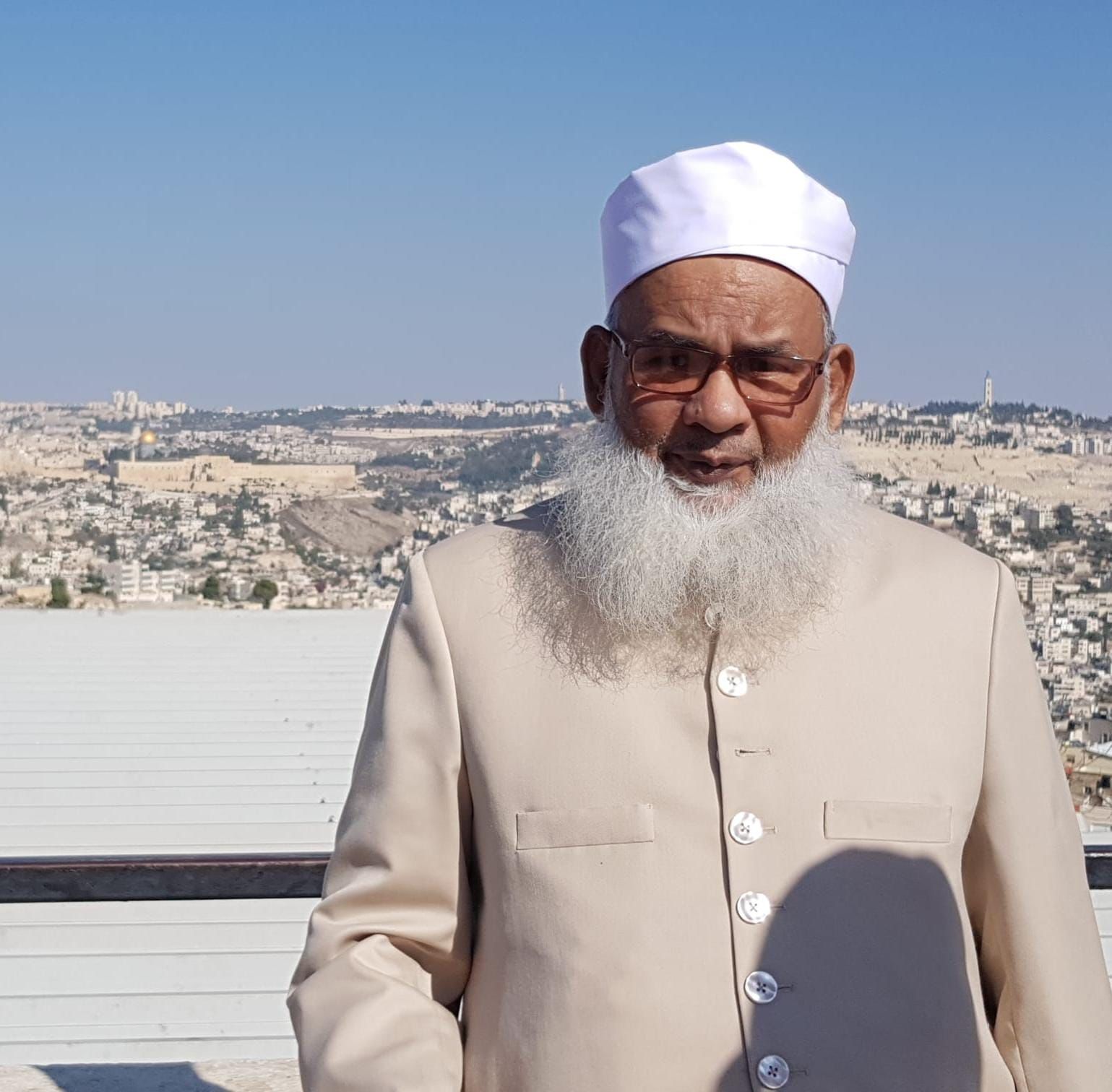

Maulānā Syed Naeem Akhtar Nadwī (RA), a portrait from his early days as a teacher at Nadwa.

Some losses do not simply make a person sad; they rearrange the inner world. They do not come as one sharp moment and then leave. They settle into your daily rhythm and quietly change what “normal” feels like. The house can look the same, but it carries a silence that was never there before, a sense of waiting, as if it still expects him to enter. The mind still turns, by instinct, towards the person who used to complete the sentence, clarify the confusion, soften the worry, and put everything back into proportion. Then, without warning, the heart remembers: the one who gave life coherence is no longer there.

How does one write about a man who was, at the same time, a father, a teacher, a mentor, and, for many people, a quiet axis of steadiness? And how does one do so without turning him into mere praise, or, on the other side, failing to show the seriousness of what he carried?

What I know is this: my father’s life was never built on performance; it was built on principle. As the scholars say, al-istiqāmah ʿayn al-karāmah (الاستقامة عين الكرامة): true honour lies in steadfastness. People did not respect him because he advertised himself. They respected him because, over decades, they saw the same sincerity, restraint, service, scholarship, and character. Those qualities do not make noise or announce themselves, but they endure. They leave behind real students, real homes, real institutions, and memories that do not easily fade.

For me, he was more than a parent. He was my closest confidant, my most trusted advisor, and my constant source of inspiration. He was the kind of father you could speak to freely, without fear of judgement. His wisdom was deep, but it was never heavy-handed. He carried it with a humility that made you feel safe, not small. I could discuss anything with him: academic questions, personal struggles, spiritual confusion. Somehow, you would leave those conversations calmer, more grounded, and more aware of what truly mattered. His patience was boundless, his composure was steady, and I never once saw him raise his voice. Even when he disagreed, he did it in a way that preserved the other person’s dignity. He had that sakīnah and waqār you only see in Rabbānī ʿulamāʾ, the kind of steadiness our elders would associate with Sayyidunā ʿUmar (RA) as mentioned by al-Bayhaqī, (even if the marfu‘ narration is Ḍaʻīf). He had a quiet dignity that did not need to be announced. It was simply there, the way fragrance fills a room without demanding attention.

To understand the man he became, it helps to begin where he began, and what shaped the world he carried within him.

Lineage

My father hailed from Sahaspur, Bijnor, a region in North India known for scholarship and religious seriousness. He was from a noble lineage of Ḥusaynī Sayyids. Among our forebears were several eminent quḍāt (judges), including one who served as a qāḍī during the reign of Aurangzeb (RA). After that era, the scholarly legacy of our family fell quiet for almost one hundred and fifty years, until my father, by Allah’s grace, revived it as the first scholar in our line since that time.

Our wider family history includes figures whose lives combined scholarship with public responsibility. The illustrious Maulānā Ḥifẓur Raḥmān Seoharwī (RA) (1900–1962), my paternal grandmother’s uncle, was a towering figure in Indian scholarship and a key activist in India’s independence movement, serving as the fourth general secretary of the Jamʿiyyat ʿUlamāʾ-e-Hind. In our present generation, a close relative, Maulānā Salmān Bijnorī, is among the senior teachers at Dārul ʿUlūm Deoband, and also the editor-in-chief of its monthly journal Darul Uloom.

Turning Toward Sacred Learning

My father’s path to religious scholarship was not one of being “sent” to study; he was drawn to it from within himself. After completing his education in Delhi, he was on a trajectory that would have taken him in a completely different professional direction. His elder brother is an accomplished civil engineer for the Delhi Development Authority and another is widely recognised for his educational work. My father could have chosen a route that promised immediate security and higher social status.

Then, quietly and steadily, something changed. A yearning for Arabic and Islamic studies began to grow in him until it became, not a preference, but a demand of the soul. He chose the path of sacred learning by conviction, and he bore the cost of that choice with dignity.

Finances were tight, and he learned hardship early: he sold sweets to cover small expenses and pocket money, gave tuition, and led prayers where he could. He would sometimes mention that, on the day of Eid, unable to afford the journey home, he would cry. He never told those memories to collect sympathy. He recalled them calmly, almost matter-of-factly, as part of what shaped him.

That loneliness did not harden him; it refined him, and sprouted as compassion. It shaped how he treated students for the rest of his life. Our home, especially on Eid, was never only a “family day”. It was also a day for those students of Darul ʿUlūm Dewsbury who could not travel. He opened the door, fed them, sat with them, made them laugh, and gave them a place where they could feel human again. Looking back, I realise it was not simply hospitality; it was loyalty to his own past. He refused to forget what it felt like to be alone.

Even after students graduated, that same spirit never left him. Many would still come to our house, and I vividly remember one occasion when I was busy with something and he called me and said, “Go to the local shop, Mullaco’s, and bring biscuits and drinks, and bring plenty of them.” At the time, I did not understand why, but it was because his students were visiting. When they came, they would often say this themselves about him: that he always received them with generosity and honour, as though they were still under his care. He used to say, quietly and firmly, that once a student graduates, the relationship should mature: تلميذ الأمس، زميل اليوم—it becomes mutual respect, shared concern, and shared responsibility for the Din. That was not a slogan. It was the way he lived, and the way he treated them.

Nadwatul ʿUlamāʾ

My father graduated from Nadwatul ʿUlamāʾ in 1978 and was, by Allah’s grace, recognised as one of its most accomplished students. Nadwa shaped him, but he also embodied what Nadwa, at its best, tries to produce: a scholar grounded in inherited sciences, intellectually awake, spiritually serious, and socially constructive.

Soon after graduation, he received an offer to study at the Islamic University of Madinah. He sought counsel from Shaykh Abul Ḥasan ʿAlī Nadwī (RA), who held him in high regard. The advice he received became a turning point. The Shaykh advised him that, for him specifically, it would not be the best decision, because his path of benefit lay elsewhere, and because the road ahead would open in a more fitting way. He told him to begin teaching at Nadwa.

My father accepted this counsel. That tells you something about him. He was not driven by the prestige of institutions, nor by the desire to collect impressive affiliations; he was driven by responsibility, and by where he could be most beneficial.

At Nadwa, after formal teacher training, he taught Sunan al-Nasāʾī, Sunan Ibn Mājah, Qaṣaṣ al-Nabiyyīn, and Muʿallim al-Inshāʾ, and he also taught fiqh works when needed. This is one of Nadwa’s strengths: a teacher’s strengths and interests are recognised, but the training is also taken seriously, and teaching is not left to personality alone. My father used to mention that in his first year of teaching, senior teachers would come in to observe lessons, to see how the class was being delivered, how the text was being explained, and how students were being built, not only instructed. He valued that culture, because it was never only about “covering a book”. It was about teaching as amanah.

In Nadwa’s internal culture, advanced books are not casually placed in the hands of a young teacher. The fact that he was entrusted with them shows the confidence his elders had in his reliability, seriousness, and scholarly maturity. His students often spoke of his ability to breathe life into texts, explaining meanings with clarity and depth. Senior teachers at Nadwa remarked that, had he stayed, he was destined to teach even higher-level works, such as Ḥujjatullāh al-bālighah and Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī.

Later, in Dewsbury, many of his students began calling him “Shaykh al-Adab”. That title did not come from rhetoric. It came from experience. They saw how he taught with precision and care, how he corrected without humiliating, and how he carried knowledge with dignity. As a student of the social sciences, I sometimes think of Pierre Bourdieu’s idea of habitus and embodiment and how close they are to the Islamic conception of adab: my father’s adab was not simply something he spoke about, but something he carried in his tone, his restraint, his posture, and the small, repeated choices of everyday teaching, until students began to absorb it without even realising they were being trained by it. And I saw an unexpected proof of that reach far from Nadwa itself: in Thailand, speaking to one of the mashāyikh in Thai, I mentioned my father’s name, and he recognised him immediately, telling me that my father had shaped his life when he first arrived at Nadwa struggling, because his manner made the environment bearable, and his teaching made difficult things feel within reach.

What many students did not see was the private discipline behind that clarity. He was extremely particular about muṭālaʿah (pre-reading) before teaching, and he would say, “This is the right of the book (ḥaqq).” At home, he kept a set time for it, even for texts he had taught for years. For him, familiarity was never an excuse to be casual; it only increased the responsibility. And he would add that this is from the barakah of ʿilm (the blessing of knowledge): when you keep returning to a text, Allāh opens further meanings.

I say this carefully, because it matters: his limits were never intellectual. They were circumstantial, and those closest to him could sense an immense reservoir that community demands and institutional timetables did not always allow him to pour out fully.

Isnād

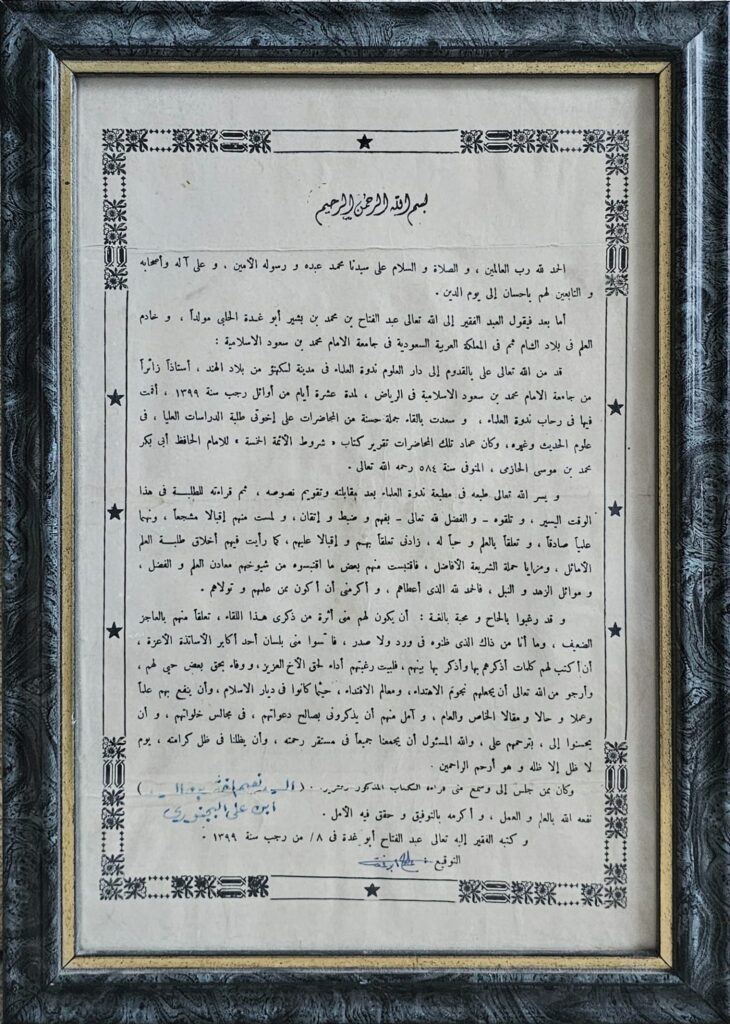

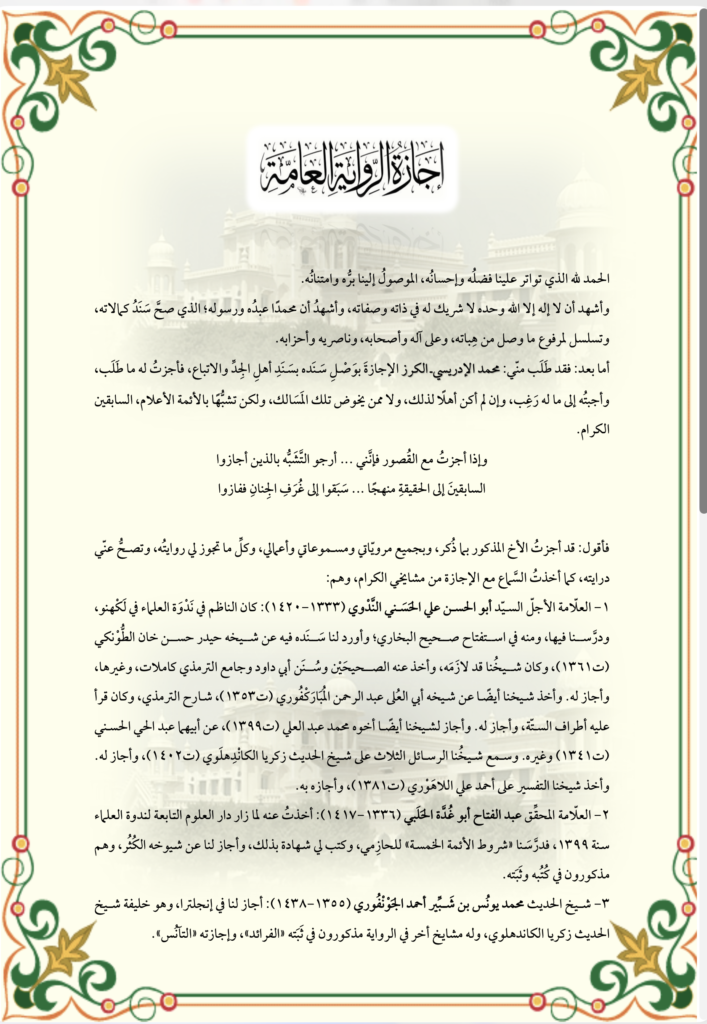

One of the most overlooked aspects of my father’s scholarly profile was the seriousness of his ḥadīth formation and the discipline of transmission that anchored him. In an ijāzah document authored by Shaykh Ziyad Tukla, my father granted authorisation in riwāyah and recorded his own mashāyikh and chains of learning. In the classical tradition, this is no ceremonial detail. It is an ethical statement: knowledge is not a personal possession; it is an inherited trust.

The ijāzah shows that my father’s scholarly exposure was not limited to India; it records gatherings and encounters with major figures beyond the subcontinent. A few of his ijāzāt and scholarly links mentioned include:

• Shaykh Hasan Habannakah al-Maydani (1908–1978): he taught the final ḥadīth of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī during a visit to Nadwa, and my father attended.

• Shaykh ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ Abū Ghuddah (1917–1997): my father benefited from him during a visit to Nadwatul ʿUlamāʾ, including instruction and certification relating to the Shaykh’s work on Shurūṭ al-Aʾimmah al-Khamsah.

Framed written ijāzah granted to my father Maulānā Syed Naeem Akhtar Nadwī from Shaykh Abū Ghuddah on Shurūṭ al-Aʾimmah al-Khamsah (8 Rajab 1399 AH)

• Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Muḥammad Zakariyyā al-Kandhlawī (1898–1982): my father gave bay‘ah in taṣawwuf and received an ijāzah in Hadith from him at Maẓāhir ʿUlūm

• Shaykh Abul Ḥasan ʿAlī Hasani Nadwī (1914–1999): my father received an ijāzah from him in Nadwa.

• Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Muḥammad Yūnus al-Jawnpūrī (1937–2017): he granted my father an ijāzah in England.

• Shaykh ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Bāz (1912–1999): in the early 1980s, on Shaykh Abul Ḥasan’s instruction, my father met him and was granted an ijāzah.

My father’s written ijāzah one of his students from Spain, drafted by Shaykh Ziyād Tukla.

England, 1980

On the advice of Shaykh Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī al-Ḥasanī al-Nadwī (RA), my father came to England in 1980 to serve, not to seek comfort. In London, he worked as an imam and chaplain in areas including Streatham, Finsbury Park, and Finchley, travelling daily by three buses to fulfil those responsibilities. In an age when people sometimes dress ordinary ambitions in the language of “daʿwah”, his life was a quiet rebuke: he did not come to perform piety or chase comfort, but to teach, serve, and carry the weight of community work when it was still unglamorous and unseen.

Later, at the request of Ḥāfiẓ Muḥammad Aḥmad Patel (RA) (1926–2016), he relocated to Dewsbury in the early 1990s. Dewsbury became the centre of his teaching and service for decades. He taught at Dārul ʿUlūm Dewsbury for nearly three decades, focusing primarily on Qurʾān translation and texts such as Nafḥat al-ʿArab and Nūr al-Īḍāḥ. His involvement with the Tablīghī Jamāʿat was also a significant strand of his life.

One small incident captured his adab with elders and teachers. Those who knew Shaykh Muḥammad Yūnus al-Jaunpūrī (RA) knew that he could be very direct, and on one occasion he spoke to Ḥāfiẓ Patel (RA) in that same frank style, to the effect that tablīgh is one path of service, but that ʿilm must also be given its full place and priority. Ḥāfiẓ Sahib later asked my father the same question three times: “What did you think of what Shaykh Yūnus said?” My father did not let it become a comment on personalities. He replied simply, “Elders sometimes get carried by what they feel, and by the concern behind their words.” That was all he said. In that one response, he protected everyone’s dignity, and he taught us what adab looks like in real life: take the lesson, honour the concern, and never turn the moment into a verdict.

Even these subjects, in his hands, were never reduced to technical instruction. He would bring language and law back to the heart, to adab, to intention, to the fear of Allah, and to the practical question of what kind of human being a student is becoming.

I say this with both gratitude and regret: I often feel that people did not take from him as much as they might have. Not because he withheld, but because communities do not always know what they have until it is gone. Some only measure scholarship by visibility, titles, or controversy. My father was neither a performer nor a polemicist; he was a teacher in the deepest sense—one who shapes souls before he shapes sentences.

It would also be dishonest to ignore the institutional realities that shaped his public role in Britain. The politics of religious spaces can be subtle, and sometimes exhausting. Those who have served within UK madrasah structures know how easily internal dynamics, loyalties, and expectations can limit a scholar’s reach, regardless of his ability. My father was not made for manoeuvring. He did not trade in alliances. He did not curate influence. He taught, he served, and he kept going. If that meant he did not “rise” to the level he deserved in certain settings, then that too is part of the story, not as complaint, but as a sober reminder of how easily sincerity is sidelined by noise. And for someone who never learned the art of “positioning”, it was quietly revealing that when a passage genuinely refused to open, even senior teachers would come to him to have it made clear.

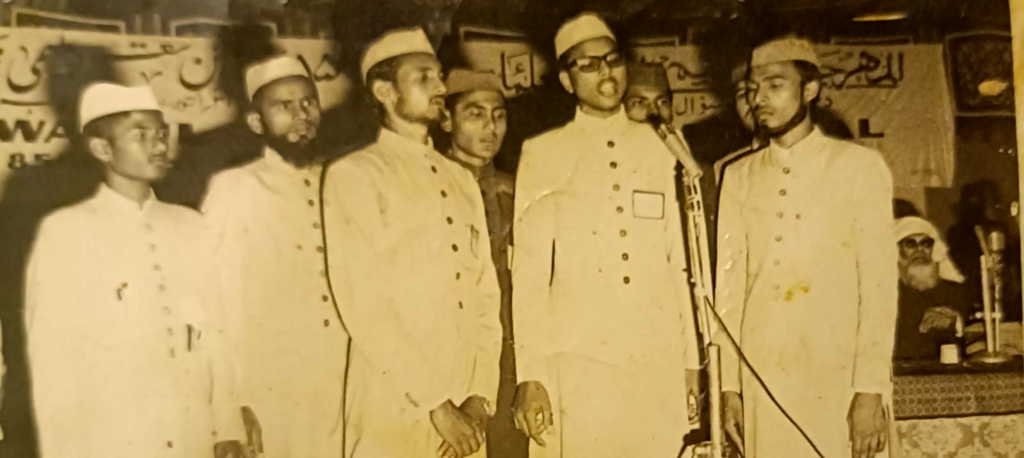

And perhaps this is what makes the “politics” element sting, because it reduced him in people’s eyes to what was visible and administrative. Among the many misfortunes of the politicisation of Muslim learning spaces is the blindsiding of salient gifts and quieter virtues among teachers. My father had a beautiful voice, and at Nadwa’s 85th celebration he was among the main voices who led the Tarānah (Nadwa anthem), a moment many people remembered for years. In close circles he would also often sing a naẓm by Maulānā Muḥammad Thani Ḥasani, not as performance, but as something that seemed to carry his inner world.

He also carried that gift with a kind of paternal discretion: he would teach it, gently, to those closest to him, correcting tone and pacing the way he corrected a line of Arabic—quietly, precisely, and without ever letting it become about display. I can say, without turning this into a story about myself, that he was my personal tutor in nasheeds, and he trained me to treat recitation as adab before it is “ability”.

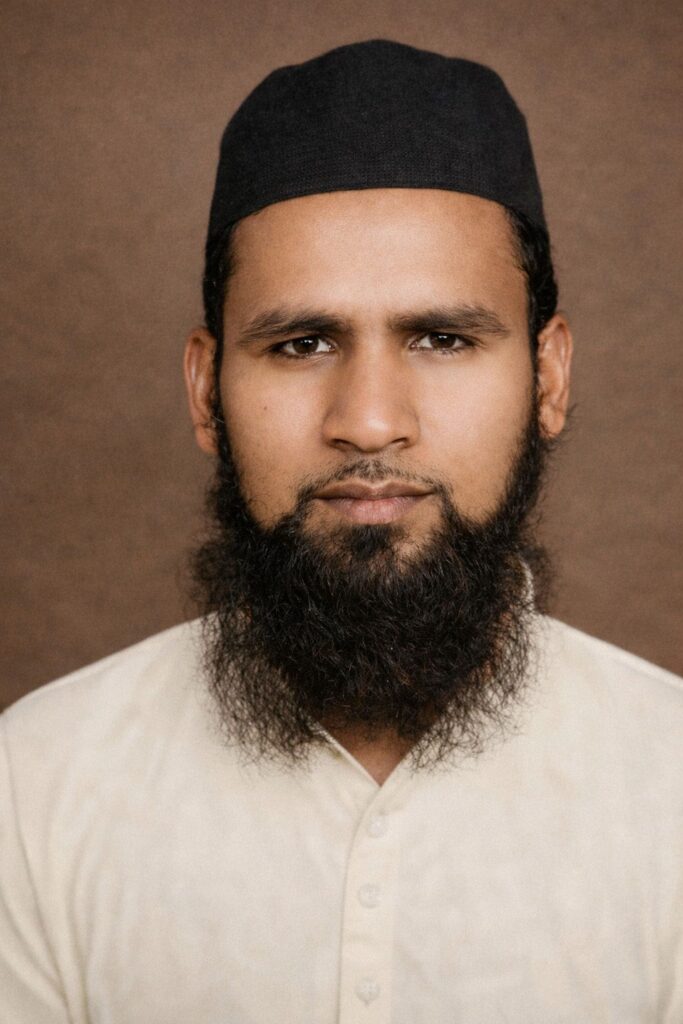

My father (second, from left) singing the Nadwa anthem (1975), with Shaykh Abul Ḥasan ʿAlī Nadwī (RA) seated on the right.

Balance, Unity, and Moral Fortitude

My father embodied the ethos of Nadwatul ʿUlamāʾ: unity without dilution, balance without compromise, and inclusivity without carelessness. He was deeply conscious of preserving the dignity of the Dīn, ensuring that religion never became spectacle in his speech or conduct.

I remember an incident from my student days that captured his juristic maturity and his instinct for harmony. I had observed some teachers at Nadwa combining prayers and asked his opinion. He replied calmly: yes, it is permissible. But where a community has an established practice and is not used to combining, it is better not to draw unnecessary attention to it. Practise what you believe is correct, but do not create discord, and do not compel others. That answer was not only fiqh. It was understanding people, and understanding how hearts are carried. Despite his knowledge, my father remained profoundly humble. He refrained from issuing fatwā hastily and would direct complex questions to qualified muftīs. That was not hesitation. It was integrity.

Love and Awe: The Balance Students Felt

People often noticed a rare balance in him: students loved him, and they were also in awe of him. Not fear, but reverence. His dignity did not crush people. It lifted them. As al-Farazdaq writes in his famous qasīdah in praise of Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn (ʿAlī ibn al-Ḥusayn):

يُغْضِي حَياءً، وَيُغْضَى مِن مَهَابَتِهِ

فَمَا يُكَلَّمُ إِلّا حِينَ يَبْتَسِمُ

“He lowers his gaze out of modesty, and people lower theirs out of awe for him;

they do not speak to him except when he smiles.”

He did not need harshness to command respect. His self-control did it. His sincerity did it. His consistent moral standard did it. At the same time, he had warmth. Many students often felt, “I am his favourite.” Not because he was partial, but because he had the capacity to make each student feel seen.

He used to say with real conviction, “My students are my ṣadaqah jāriyah; their work is my legacy.” He did not say it as a slogan. He lived it.

Home and Tarbiyah

At home, his character became even clearer, because there was no public audience.

My mother once accidentally added salt twice to the food. I reacted. Before I could say anything, he stopped me with a look, as though even my tone would be an act of disrespect, and he said calmly, “Eat what you have and do shukr.” He ate a full plate without complaint. Only later, when my mother tasted the food herself and realised what had happened, she was shocked at how he managed to eat it so normally. He did not turn it into a lecture. He simply embodied patience. That was his style of love: not the loud reassurance of words, but the steady education of presence. I felt that same love most sharply when I led Tarāwīḥ at Dārul ʿUlūm Dewsbury. Despite having suffered a stroke the year before, he made it his practice to come every single night and pray behind me. Medically, he had every excuse to stay home, to rest, to preserve himself. Yet he still came—quietly, faithfully—because for him, encouragement was not a speech; it was showing up, even when the body had begun to protest.

His tarbiyah was never built on fear; it was built on clarity and consequence. He would say, “You have freedom of choice, but you do not have freedom from the consequences of your choices.” That sentence shaped the moral structure of our home. It taught accountability without crushing the spirit.

He also had foresight. In 1995, when computers were rare in homes, he ensured that our household had one. He wanted his children to be prepared, not dazzled.

He did not measure blessing by property or savings. He would say that he owned no house, no plots, no investments, and that he had spent his life paying rent, yet by Allah’s grace we never felt deprived. And when something painful happened, he would steady himself quickly with one thought: it was written long before the creation of the universe, and nothing we could have done would have changed it. “So what?” he would say, not out of coldness, but out of īmān. He refused to live in resentment. He accepted the decree, took the lesson, and moved forward. Those who knew him personally knew of the various trials and tribulations he was subjected to, yet they also saw something rarer: a steadiness that did not sour, and an adab that did not crack under pressure. His tawakkul was not something he spoke about; it was something he lived, and with time its barakah became visible, especially in the way Allah carried his children and opened doors for them to contribute in their own lanes. He used to teach us, without turning it into speeches, that sabr is not passive: it is dignity under strain, and trust that Allah does not waste what is borne for His sake.

That same principle—choosing what would form us, even when it cost him—also shaped one of the biggest decisions he made as a father.

In fact, the clearest example of that principle was the educational choice he made for us: sending me and my brother, Maulānā Syed Muʿāwiyah ʿAlī Nadwī, to study at Nadwa as well. He wanted us to taste that world directly, not as a story, but as lived experience. And it was, in every sense, a sacrifice from him: he chose years of having his two sons away from him, not because that distance was easy, but because he believed our formation mattered more than his comfort. Looking back, I recognise what that decision cost him emotionally. I also recognise what it gave us.

He also had refined taste and presence and carried himself with scholarly dignity: sherwānī and ʿimāmah, a neatly kept beard, and a constant care to smell good and appear presentable, as though adab should be visible before a single word is spoken. He enjoyed fragrance, yet he was sensitive to others. A senior teacher, Maulānā Yūsuf Darwan, disliked the strength of the perfume Shamāmah al-ʿAnbar. My father liked it, yet he stopped using it. On the surface it is a small courtesy, but in truth it is a moral signature. It reveals a person whose ego does not insist on domination in even the smallest issues.

Alongside his scholarship, my father was also an accomplished poet. His poetry was not an accessory. It was an extension of his interior life. It carried devotion, reflection, longing, and the quiet awareness of Allah that marked his conduct. Those who only knew him as a teacher of texts did not always realise how sensitive his heart was, and how naturally language came to him when he wanted to express what ordinary words struggle to hold.

Ḥujjiyyat al-Ḥadīth

Among the works dearest to me is his thesis on Ḥujjiyyat al-Ḥadīth (The Evidentiary Authority of Hadith), handwritten during his Nadwa years and praised by senior teachers and scholars there for its seriousness, clarity, and intellectual sobriety. For years, he was reluctant to publish it. Not because he doubted it, but because he did not chase publication as a badge.

A short time before he passed away, I sought his permission once again, and he granted it. In his final weeks, I sat with him and read the entire work to him. It was one of the most intense and tender experiences of my life. It was not only the reading of a text; it was sitting with his mind, his discipline, his care, and the sincerity that runs underneath a scholar’s arguments when the work is written for Allah. I said to him clearly, “In shāʾ Allāh, I am getting this published.” He was visibly pleased and deeply moved.

By Allah’s permission, we are now working on publishing that work. Alongside it, we are preparing to publish articles and tributes from his students and those who benefited from him. Many of them knew him in a different capacity: as the teacher who shaped their faith, as the mentor who carried their burdens quietly, as the poet whose lines softened their hearts, and as the scholar whose character taught them as much as his lessons.

For anyone who wishes to contribute, we welcome articles and reflections in Arabic, Urdu, and English. Please send submissions to: snaeemnadwi@gmail.com or huzaifahnadwi@gmail.com

A Few Days Before He Left

A few days before he passed, we had a small gathering at home that now feels like a gift placed into our hands before separation. Present were my father-in-law, Maulānā Faẓlur Raḥīm Mujaddidī (a classmate of my father from Nadwa), my brother, and Maulānā Yūsuf Sacha (a teacher at Dārul ʿUlūm Dewsbury). Towards the end of that gathering, my father said a couplet that has stayed with me as both theology and solace:

لپٹ جاؤں گا قدموں سے تو سینے سے لگا لینگے

میرے آقا(ﷺ)کو عادت ہی نہیں ٹھوکر لگانے کی

If I fall at the feet of the Prophet (ﷺ) and cling to them, he will draw me close to his blessed chest,

for the Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) is not one to turn anyone away or push them aside.

In the final period of his life, he developed a fever. In those moments, a ḥadīth came to mind: that no Muslim is afflicted with harm except that Allah removes sins through it as leaves fall from a tree. It did not remove sadness, but it saved sadness from hopelessness.

As his time drew near, my brother, Maulānā Syed Muʿāwiyah ʿAlī Nadwī witnessed that he raised his shahādah finger, his gaze fixed above, and recited the full testimony of faith: “Ashhadu an lā ilāha illallāh wa ashhadu anna Muḥammadan Rasūlullāh.” He also sought forgiveness from my mother with a gesture. His passing was serene. His soul departed almost imperceptibly, as though sleep simply deepened and the next world opened.

After his burial, Maulānā Ghulām Desāʾī, Imām of Masjid-e-ʿUmar (Dewsbury), visited his grave. With deep reverence, he shared that he sensed a distinctive fragrance emanating from the grave. We hold such things with hope, not with arrogance. If it is a sign, it is Allah’s generosity.

Maulānā Syed Naeem Akhtar Nadwī’s (RA) resting place (Dewsbury).

After his passing, people from different backgrounds came to visit and pay respects. That diversity itself testified to his openness. He held principles firmly, but he did not build identity out of hostility. People felt safe around him, and that safety is not a minor legacy; it is a rare one.

What remains, above all, is his character.

He taught, and his students became living continuations of his work.

He served, and the community still feels the imprint of his steadiness.

He raised a family without harshness, without hypocrisy, and without moral theatre.

He lived with principles that cost something, and he paid that cost without complaint.

And for me personally, the hardest truth is this: I have lost a father, but I have also lost a refuge, someone I could debate with, confide in, learn from, and return to. That is a unique grief. The intellect mourns, the heart mourns, and even the daily rhythm of life mourns.

The truth is that time does not become the remedy; the weight on the heart only grows heavier day by day.

یوں تو اشکوں سے بھی ہوتا ہے الم کا اظہار

ہائے وہ غم جو تبسم سے عیاں ہوتا ہے

Grief can be expressed even through tears,

but alas, there is a sorrow that becomes visible through a smile.

May Allah have mercy upon you, Abbu.

Your love, your dignity, and your quiet guidance will remain with us forever.