By Syed Huzaifah Ali Nadwi, Cambridge.

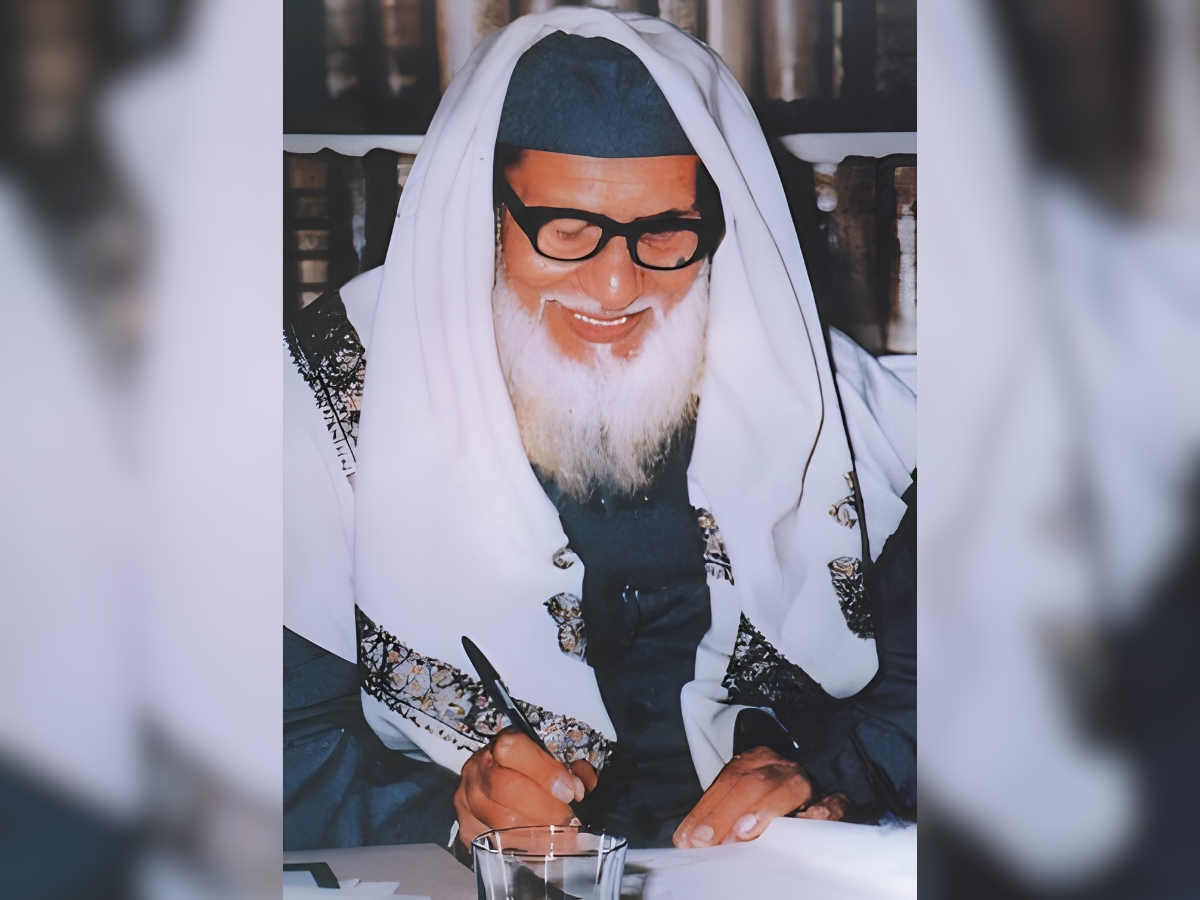

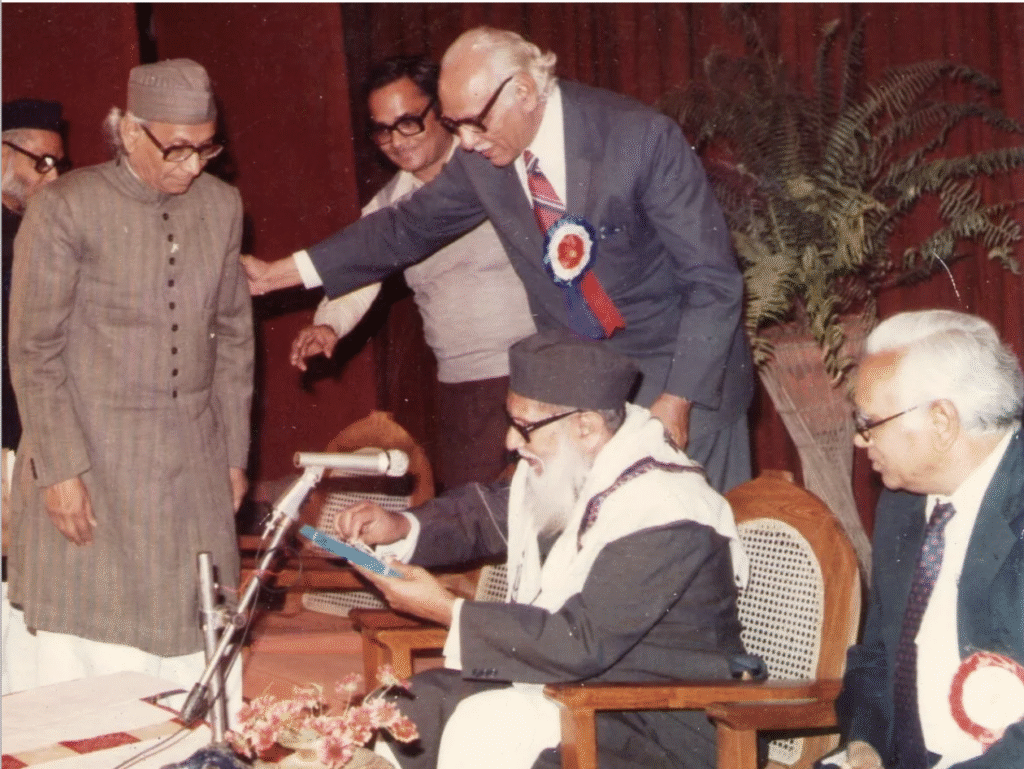

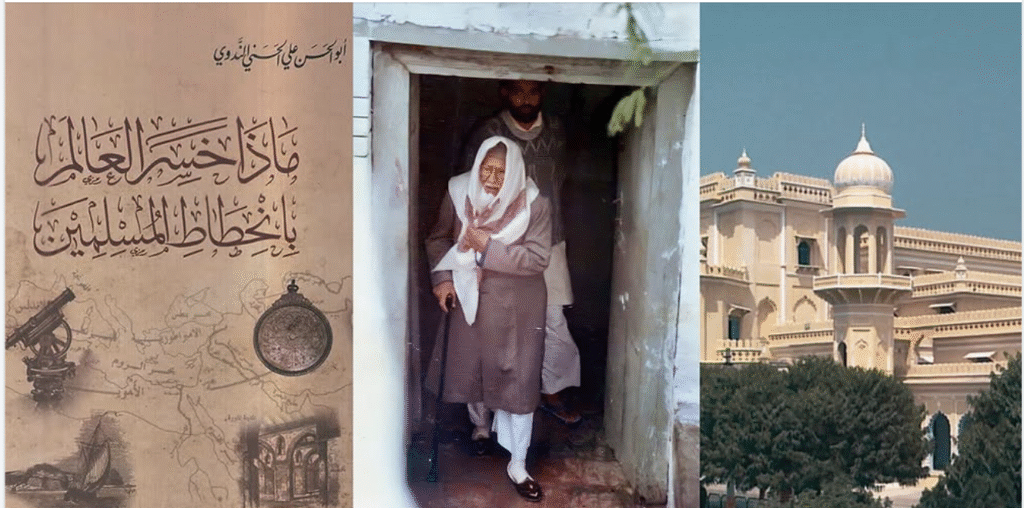

I recently received a message critiquing a passage attributed to Shaykh Abul Hasan Ali Nadwi (d. 1999) from his renowned work Mādhā Khasira al-‘Ālam bi Inḥiṭāṭ al-Muslimīn (What the World Lost Due to the Decline of Muslims). This message alleged that Shaykh Nadwi’s reflections on the decline of the Ottoman Empire and the Muslim world were shaped by modernist ideologies. After reviewing the critique, it became apparent that the individual had likely not read the book thoroughly—especially in its original Arabic, where Shaykh Nadwi’s objectives and intentions are more transparently conveyed. It is unscholarly to focus on isolated excerpts without engaging with the complete context. Given this, I felt compelled to offer a more nuanced explanation of Shaykh Nadwi’s views.

It is crucial to remember that Mādhā Khasira al-‘Ālam bi Inḥiṭāṭ al-Muslimīn (translated into English as Islam and the World) was written in 1951 and has been highly respected by scholars from various schools of thought for more than seventy years. The work transcended sectarian divisions and became a major contribution to Islamic thought. Given its long-standing positive reception and the fact that it has been translated into over ten languages, including Turkish, Urdu and French, it is surprising that after so many years, someone would suggest that Shaykh Nadwi’s perspective was coloured by modernist ideologies. Such claims are not only misleading but also dismiss the broad recognition this work has received over decades.

Addressing the Key Points

Several highlighted sections of the critique seem to have led to misunderstandings. I will address these points below, offering greater context from the same book to clarify Shaykh Nadwi’s perspective and demonstrating that these critiques overlook the overall message of his work.

“They had a glorious opportunity of stealing a march on Christian Europe in heralding the New Age and guiding the world along the path of enlightened progress.” (page 94, Islam and the World)

This passage has been misinterpreted as advocating for a Western-style “enlightened progress.” However, Shaykh Nadwi’s reference to “enlightened progress” should not be taken as an endorsement of secularism or Western values. Instead, it expresses his regret that the Ottoman Empire—and by extension, the Muslim world—missed the chance to lead the world in intellectual, scientific, and spiritual progress, all within an Islamic framework. Shaykh Nadwi was not calling for Muslims to follow the West, but rather to reclaim their historical role as pioneers of knowledge, guided by Islamic principles, as they had done for over a thousand years prior.

Additionally, Shaykh Nadwi’s use of the term inḥiṭāṭ refers not only to a political or military decline, but to the decline in learning and the practice of faith, particularly when compared to earlier generations of Muslims. His argument was that the Muslim world’s fall accelerated as Muslims distanced themselves from their tradition. Shaykh Nadwi highlighted that this process of decline wasn’t because of Islam, but rather due to Muslims moving away from the very teachings that once nurtured a vibrant intellectual society.

In a later section of the book, Shaykh Nadwi criticises the West’s materialism, stating, “Religion was ostracized and secularized; moral enthusiasm was crushed under the weight of material cravings. The religious instinct of Eastern peoples, too, which was the pivot of their lives, was seriously impaired.” (page 177). This demonstrates Shaykh Nadwi’s conviction that the West, in pursuing material success, undermined the moral and spiritual fabric of society. By sidelining religion, Western civilization may have gained some temporal material benefits but had ultimately lost its higher purpose and spiritual direction. He consistently emphasises that true progress must balance material advancements with moral and spiritual integrity.

Shaykh Nadwi goes further to challenge the West, asking whether its scientific and technological advancements have truly brought happiness to humanity. He argues that by separating quantitative progress from qualitative, ethical improvements, the West has sacrificed higher values for practical gains. Despite monumental advances in science, Shaykh Nadwi contends that this progress has brought about a state of “fear, greed, loneliness, and spiritual despair” (page xiv). He stresses that scientific achievements alone are meaningless without corresponding improvements in human morality.

In contrast, Shaykh Nadwi calls on Muslims to rebuild society on the foundation of Islamic faith and its way of life. He emphasises that the revival of the Muslim world lies not in reforming Islam itself, but in Muslims “reforming themselves by creating that inner awakening, that permanent consciousness, and that sense of responsibility in all their thoughts and actions which distinguished the lives of the Companions of the Prophet of Islam.” (page xiv). This inward renewal is the key to revitalising the Muslim world and providing a counterbalance to the spiritually hollow progress of the West.

“The greatest error the Ottomans made was that they allowed their minds to become static.” (page 95, Islam and the World)

This statement is misunderstood as a critique of Islamic tradition. However, Shaykh Nadwi was not criticising tradition itself; he was addressing the intellectual stagnation that had taken hold of the Muslim world’s educational and scholarly institutions. His critique was of the staleness of thought, not tradition, and his plea was for Muslims to reinvigorate their intellectual pursuits while preserving their spiritual foundations. Similar concerns were expressed before him, especially among late Ottoman traditionalist thinkers, including Mustafa Sabri (d. 1954), Ibn Badran (d. 1927), and others.

The interlocutors and critics Shaykh Nadwi was refuting were the actual modernists. They suggested that Islam itself had led to intellectual stagnation. However, Shaykh Nadwi’s argument was that normative Islamic practice, along with its regional cultural expressions, fostered a deep love of learning and intellectual inquiry. When Muslims gradually distanced themselves from their tradition, the decline accelerated. The more Muslims study Islam and reconnect with their tradition, the more intellectual activity and inquiry their communities will encourage and appreciate.

Just a few pages later after the excerpt in question, Shaykh Nadwi praises earlier Islamic scholars for their immense contributions to Islamic thought. He highlights figures such as Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi Mujaddid Alf Thani (d. 1624) and Shah Waliullah Dehlawi (d. 1762), who transcended the intellectual limitations of their times and made lasting contributions. Shaykh Nadwi writes, “Only a few were above the low intellectual level of their age… Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi… left a lasting impression on the entire Muslim world. His Letters made a valuable contribution to Islamic religious thought. Another prominent figure was Shah Waliullah Dehlawi, who wrote unique works in various fields.” (page 98). This reinforces Shaykh Nadwi’s deep appreciation for tradition, while simultaneously advocating for a return to the intellectual dynamism that once defined Islamic scholarship.

“Europe, meanwhile, was making colossal scientific and industrial progress.” (page 100, Islam and the World)

The mention of Europe’s advancements is taken in the critique sent to me as an endorsement of Western models of progress. However, Shaykh Nadwi was not advocating for the wholesale adoption of European thought. Rather, he was pointing out the contrast between Europe’s advancements and the intellectual stagnation in much of the Muslim world. His intent was to remind Muslims of their own historical legacy of scientific and intellectual leadership and to urge them to rediscover that tradition.

Elsewhere in the book, Shaykh Nadwi critiques Europe’s moral decline, stating,

“The coupling of moral and religious depravity with phenomenal progress in the scientific and industrial fields led to the creation of a striking disparity between power and ethics. Men learnt to fly in the air like birds and to swim in the water like fish; but they forgot how to walk straight on the earth.” (pages 176-177).

This critique underscores that while Europe made substantial material progress, it came at the cost of moral and ethical decay, which had detrimental effects on society’s inner peace. The critique fails to acknowledge these deeper reflections within the book.

“The Muslims, alas, neglected not minutes but centuries, whereas the European nations realized the value of time and covered the distance of centuries in years.” (page 100, Islam and the World)

Shaykh Nadwi’s concern was that the Muslim Ummah had lost its sense of urgency in pursuing knowledge and progress, something deeply ingrained in the Islamic tradition. His reference to Europe “covering the distance of centuries in years” was a call for Muslims to reawaken to the importance of time and to once again become leaders in intellectual and spiritual development. His message was not to chase after Europe, but to rediscover the essence of Islamic vitality and purpose. As he emphasised in a later passage,

“There is absolutely no need for a new religion, a new Canonical Law or a new set of moral teachings. Like the Sun, Islam was, is, and will be timeless. The Mission of Prophet Muhammad is endowed with the quality of timelessness.” (Page 184).

This further underscores that Shaykh Nadwi’s argument is not a call for modernist imitation, but a plea to revive the Islamic tradition of knowledge and spiritual excellence—something the critique seems to have missed by focusing on isolated passages.

The Importance of Context in Scholarship

The critique of Shaykh Abul Hasan Nadwi’s Mādhā Khasira al-‘Ālam reflects a common problem in modern scholarship, where texts are divorced from their broader context. True scholarship requires a deep engagement with the entirety of a work, within its historical, cultural, and linguistic context. The author of this critique would perhaps concur with me on this, as he often stresses the importance of such engagement when critiquing Western thought. It is surprising, then, that the same level of consideration is not extended when engaging with the works of fellow Muslims.

Moreover, modernism, as a philosophical stance, is based on rejecting or at least looking down on traditional attitudes and norms. Anyone familiar with Shaykh Nadwi’s writings knows he was a Sufi and a staunch advocate of normative and traditional Islamic learning. The criticism overlooks the fact that Shaykh Nadwi wrote this book when he was in his early thirties. Like all scholars, his thoughts and positions evolved with age and maturity. Criticising his entire body of work—which spans over six decades—based on a few decontextualized statements from this early period is a serious misjudgment.

While I have no doubt about the author’s intentions, the use of overly complex and exaggerated language in the critique, —such as referring to the work as “a manifesto of myopic philosophical and historical crudity”—reflects a trend where convoluted wording is employed to appear authoritative. Unfortunately, this often obscures the message rather than clarifying it, contradicting Islamic adab (etiquette) and literature, both of which emphasise clarity, accessibility, and sincerity. While this type of language may seem intellectual, it often obscures the real message and hinders productive dialogue.

As a student of Shaykh Abdul Hakim Murad, and having studied at Cambridge Muslim College, I have witnessed firsthand how these sentiments are shared by scholars dedicated to reviving intellectual excellence in the Muslim world. Institutions like Nadwatul Ulama and Cambridge Muslim College aim to foster excellence in both intellectual and academic fields while remaining grounded in the Islamic tradition. The establishment of such institutions is a response to the reality that Muslims have, in recent times, fallen behind in various fields of knowledge. If one were to label such efforts as “modernist” simply because they engage with contemporary intellectual disciplines, it would be a fundamental misunderstanding of the purpose behind them.

Similarly, Shaykh Abul Hasan Nadwi’s Mādhā Khasira al-‘Ālam bi Inḥiṭāṭ al-Muslimīn was never a call to adopt modernist ideologies. Rather, it was a deeply insightful analysis of how Muslims, through neglecting both intellectual rigour and spiritual refinement, gradually declined while Europe, by contrast, advanced in various spheres, particularly science, philosophy, and governance. His reflections were grounded in a desire to revive the Islamic tradition of intellectual leadership and spiritual vitality. Had the Muslim world remained at the forefront, there would have been no need for institutions like Cambridge Muslim College, nor would there be any reason for such writings as Mādhā Khasira al-‘Ālam.

In sum, Shaykh Nadwi’s work has stood the test of time for over seventy years, being praised and accepted by scholars across the spectrum of Islamic thought. His reflections were not a call to adopt modernist ideologies but a heartfelt plea for the Muslim ummah to revitalise its intellectual and spiritual life while remaining firmly rooted in Islamic principles.

May Allah grant us the wisdom to understand our scholars’ intentions and the ability to carry forward their legacy in ways that are true to our religion. May He guide us to become a community that is intellectually vibrant, spiritually strong, and always seeking His pleasure. Āmīn.