Syed Huzaifah Ali Nadwi

Cambridge, UK

It is with immeasurable joy and a deep sense of responsibility that I present the English translation of the Urdu work Fikr-e Yūnus, published as Muḥammad Yūnus of Jaunpūr – A Critical Study of the Intellectual Contributions of the Ḥadīth Authority from Saharanpur, authored by Dr Muḥammad Akram Nadwī. This essay is being shared ahead of the book’s publication in order to introduce readers to the man at its centre and to the concerns that guided this translation.

From the outset, my primary aim has been to preserve, as faithfully as possible, the depth and nuance of the original while making it genuinely accessible to English-speaking readers. That has required slow work: carefully rendering technical discussions, deciding where to break complex sentences without flattening them, and—perhaps most visibly—meticulously adding full diacritics to the Arabic throughout. In the original Urdu edition, much of the Arabic material lay in the footnotes. After long reflection, I chose to move most of these passages into the main body of the text. I wanted readers to feel the weight of the Arabic citations as part of the argument itself, not as something left to the margins.

Because this is the first comprehensive study of Shaykh Muḥammad Yūnus Jaunpūrī’s life and thought to appear in English, it seemed essential that the translation be complete. Every section—including the most intricate discussions of isnād, conflicting narrations and tarjīḥ—has therefore been rendered in full, with as much precision as I could manage, so that the work remains accessible to serious readers without ceasing to be demanding in the way that such a subject ought to be.

I owe more thanks than I can properly express. I am deeply grateful to Dr Muḥammad Akram Nadwī for entrusting me with the task of translating this study. My heartfelt thanks go to Mawlānā Hāroon Anīs Maẓāhirī, who sat with me over the Arabic repeatedly, catching slips and helping to keep the text faithful. I am also grateful to Muntaha Publishers, to Mawlānā Muzzammil ʿAlī Nadwī—whom I have known since my student days in Nadwatul ʿUlamāʾ—and to Ustadh Junaid Greer; their trust and cooperation have been crucial in bringing this book to fruition.

The delays in completing this translation are tied to other strands of my own journey: the closing stages of my Master’s degree, the beginning of my PhD, and the normal pressures of teaching, travel and family life. Yet the work never left my mind. During repeated visits to Maẓāhir ʿUlūm, the presence of Shaykh Yūnus (RA)—his manner, his method, his quiet intensity—left a mark that began to overlap with my own academic concerns. My doctoral research, Qur’anic Interpretations and Muslim Intellectual Dynamics in Colonial South Asia: The Case of Shāh ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz (d. 1823) and the Madrasah Raḥīmiyyah, has only sharpened my sense of how often his approach resonates, in both spirit and method, with the thought of Shāh Walīullāh and Shāh ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz: a carefully measured middle path that refuses the comfort of polar extremes in belief, practice and scholarship.

I am often reminded, in this context, of a simple line that our elders repeat: ṣuḥbat al-kirām tarfaʿ al-maqām – keeping the company of the noble raises a person’s rank. Al-Shīrāzī gives this a memorable image in Rawḍat al-Ward. He describes a man entering the ḥammām and seeing people anointing themselves with a perfumed clay that had been soaked in water and rose-petals. He addresses the clay and says:

رَأَيْتُ الطِّينَ فِي الحَمَّامِ يَوْمًا *** بِكَفِّ الحِبِّ أَثَّرَ ثُمَّ نَسَّمْ

فَقُلْتُ لَهُ: أَمِسْكٌ أَمْ عَبِيرٌ؟ *** لَقَدْ صَيَّرْتَنِي بِالْحِبِّ مُغْرَمْأَجَابَ الطِّينُ: أَنِّي كُنْتُ تُرْبًا *** صَحِبْتُ الْوَرْدَ، صَيَّرَنِي مُكَرَّمْ

أَلِفْتُ أَكَابِرًا وَازْدَدْتُ عِلْمًا *** كَذَا مَنْ عَاشَرَ الْعُلَمَاءَ يُكْرَمْ

I once saw clay in the bathhouse one day, In the palm of the beloved there lingered a trace, then a breath of fragrance.

I said to it, “Are you musk or some fine perfume? You have made me, through this love, utterly enamoured.”

The clay replied, “I was nothing but earth; I kept the company of the rose, and that companionship made me honoured.

I grew familiar with the great ones and increased in knowledge – And so it is: whoever lives among the scholars is honoured.”

For those of us who were allowed even a little time in the circles of our mashāyikh, the meaning is very clear. I spent close to a decade studying at Nadwatul ʿUlamāʾ in India, under a number of senior teachers, and I was able to visit other centres of learning frequently – including repeated visits to Maẓāhir ʿUlūm and to the majālis of Shaykh Yūnus. Whatever benefit there is in this translation comes, in truth, from that company: from the hours in which we were simply allowed to sit, listen, read, and watch how our elders handled texts and spoke about dīn. This book is one small attempt to pass something of that suhbah on to readers who may never have had the chance to sit in those gatherings themselves.

Any attempt to understand that balance must also acknowledge, however briefly, the towering presence of his own teacher, Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Mawlānā Muḥammad Zakariyyā Kāndhlawī (RA). For decades at Maẓāhir ʿUlūm Saharanpur, Shaykh Zakariyyā stood at the centre of the ḥadīth tradition—author of Awjaz al-Masālik on the Muwaṭṭaʾ, mentor of generations, and the living embodiment of a curriculum where rigorous scholarship and lived spirituality belonged together. The ethos he shaped—sobriety in narration, care in attribution, and an almost tangible sense that teaching Bukhārī and Muslim is itself an act for which one will answer before Allah—formed the air that Shaykh Yūnus breathed. He grew up within that climate: first as a student, then as a close disciple, and finally as one of the most distinguished heirs to that legacy.

A Life Sketched in Milestones

Shaykh Muḥammad Yūnus ibn Shabbīr Aḥmad was born on Saturday 2 October 1937 (25/26 Rajab 1356 AH) in Jaunpur, Uttar Pradesh. His mother passed away when he was only five years old, and he was raised thereafter by his maternal grandmother, whose piety and affection he remembered with gratitude throughout his life. He began his formal Islamic studies in Jaunpur at Madrasah Ḍiyāʾ al-ʿUlūm under Mawlānā Ḍiyāʾ al-Ḥaq Fayḍābādī—a teacher whose favour and kindness he never forgot.

In Shawwāl 1377 AH, he travelled to Saharanpur and enrolled at the famous seminary Maẓāhir ʿUlūm, where he studied under a number of major scholars, most notably Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Mawlānā Muḥammad Zakariyyā Kāndhlawī and Mawlānā Asʿadullāh Rāmpūrī. From both he received not only formal training in hadith but also ijāzah in taṣawwuf and a pattern of life in which study, worship and service were woven together. He completed his Dawrah Ḥadīth and graduated in 1380 AH, already recognised for his unusual command of the texts and for a memory and insight that his teachers regarded as exceptional.

A year later, in Shawwāl 1381 AH, he was appointed as a teacher at Maẓāhir ʿUlūm. Over the years that followed he taught a wide range of central works: Sharḥ al-Wiqāyah and Hidāyah in fiqh, Uṣūl al-Shāshī, Mukhtaṣar al-Maʿānī and Nūr al-Anwār in uṣūl and balāghah, Mishkāt al-Maṣābīḥ and the four Sunan, Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, and both Muwaṭṭaʾ Mālik and Muwaṭṭaʾ Muḥammad. Then, in Shawwāl 1388 AH, while some of his own teachers were still alive, Shaykh Zakariyyā appointed him Shaykh al-Ḥadīth and entrusted him with teaching Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī. For roughly half a century thereafter he taught Bukhārī with a devotion and rigour that left its mark on thousands of students across India, the Middle East, Africa, Europe and beyond.

His written legacy became more visible in his later decades. Among the most important works that have so far reached print are al-Yawāqīt al-Ghāliya, a multi-volume collection of his research notes, answers, and treatises—mostly in ḥadīth—and Nibrās al-Sārī ilā Riyāḍ al-Bukhārī, the opening volumes of his Arabic commentary on Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī. Both of these projects owe a great deal to the tireless editorial and organisational efforts of his student Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Mawlānā Ayyūb Surtī, who worked for many years to collate, verify, and prepare these materials for publication. Alongside these stand his marginal notes and reflections on the four Sunan, on Mishkāt al-Maṣābīḥ, Badhl al-Majhūd, Fatḥ al-Bārī and Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim. Much of this material is still being gathered, edited, and readied for wider circulation by his students and close associates.

He lived simply in a small room within the seminary, surrounded by books. He never married, not out of any opposition to marriage but out of a conscious decision to devote himself entirely to teaching, reading and writing. Those who were close to him speak of a life of zuhd and charity: gifts quietly redirected, stipends declined, manuscripts written on the backs of old envelopes when paper could not be afforded, and a consistent preference for hardship when the alternative involved even a hint of compromise.

He returned to his Lord on Tuesday 11 July 2017 / 17 Shawwāl 1438 AH in Saharanpur, after a final cycle of teaching, travelling to the Ḥaramayn, and visiting the United Kingdom. His janāzah was attended by crowds of a scale rarely seen in the city, and he was buried—as he had requested—near his beloved teacher Mawlānā Asʿadullāh Rāmpūrī in the Ḥājī Shāh graveyard.

A Letter Sealed for Forty Years

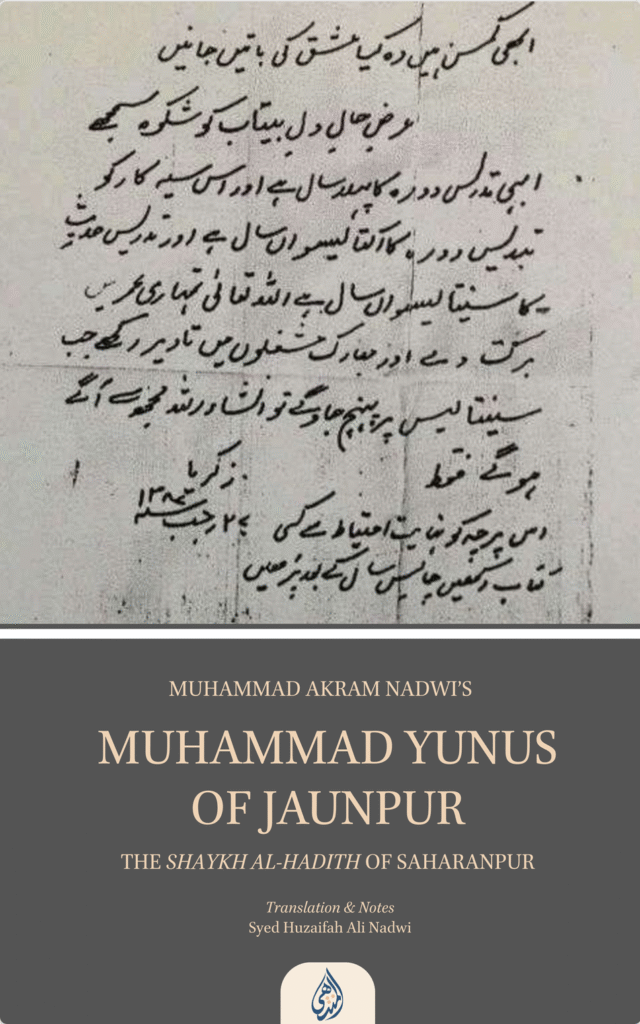

Among the many testimonies to his rank in hadith, one document has acquired a special place in the memory of his students. On a particular Friday, Shaykh Zakariyyā completed his Bukhārī lesson in the morning, while the young Shaykh Yūnus had scheduled his own Bukhārī dars for later the same day. When he learnt that his teacher would prefer not to have another Bukhārī class immediately after the completion of the book, he felt uneasy and wrote to apologise and seek guidance.

The reply came as a short handwritten note. Its content was not to be read immediately. Instead, Shaykh Zakariyyā instructed him to seal the letter and open it after forty years. The document remained in Shaykh Yūnus’s possessions, carefully preserved. Many decades later, when he fell gravely ill and asked that his room be searched for important papers, the note was found and finally opened. In it, his teacher expressed remarkable confidence in his student’s future in the field of hadith, to the extent of predicting that after a set number of years he would surpass him in certain aspects of the discipline and that difficult questions in hadith would be resolved at his hands.

A facsimile of this Urdu letter now appears on the cover of the English edition of this book. The image used for the cover is based on the scan first made widely available in the obituary of Shaykh Muḥammad Yūnus Jownpūrī on Islamic Portal (islamicportal.co.uk), and it is reproduced here with full acknowledgement of that source. It felt fitting that the book should open visually, as well as intellectually, under the shadow of that trust: the handwriting of the teacher, the patience of the student, and a forty-year span of work between the two.

A Discipline of Reading

Alongside the technical labour of translation, students and colleagues have repeatedly asked me not only for biographical detail about Shaykh Yūnus, but also for an account of his method: how he read, how he handled evidence, how he understood the ḥadīth corpus and, above all, how he approached Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī. The book you now hold is, in one sense, a sustained answer to those questions. This introduction is only a sketch of the discipline of reading that I saw operating in his presence, so that the biography that follows is read not merely as a story but as an invitation into a certain scholarly conscience.

There are teachers whose presence is felt through constant speech, and others whose presence is felt through the way they move inside a text. Shaykh Muḥammad Yūnus al-Jaunpūrī belonged unmistakably to the second kind. Outwardly, there was often an almost disarming quiet. Beneath that quiet lay a firm, non-negotiable demand: do not end a discussion at the comfort of a secondary citation; do not repeat a paraphrase as though it were the original; and do not detach a report from the place in which its author deliberately set it down.

In his company, the ḥadīth corpus was not a storehouse of “useful quotes”. It was an amānah. To place a sentence in the mouth of the Prophet ﷺ without warrant was, in his view, not a small slip but a wound to the very mechanism that protects the religion from devout invention. The habit he modelled was simple to describe and hard to live by: name the earliest recoverable source you are actually using; give the wording, not a softened memory of it; indicate the context in which it appears; and when a line cannot be reliably found, admit it, and stop asking the dīn to carry it. A great deal is cured by that single discipline: our appetite for slogans, our impatience with context, and our tendency to dress deep-rooted habit in the clothes of “authentic tradition”. What others often treat as a mark of piety—“everyone says this, so it must be true”—he treated as a reason to return quietly to the shelves.

Nowhere was this clearer than in his approach to Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī. Under his reading, the book ceases to be a long catalogue of sound reports and emerges as an authored argument. The chapter headings, the tarājim al-abwāb, are not casual labels pasted above piles of narrations. They are theses: sometimes stated openly, sometimes framed as questions, sometimes compressed into a line that looks deceptively simple. To enter a chapter, in his method, is first to restate in one’s own words what the heading is actually claiming. Only then does one turn to the reports and ask how they have been arranged in service of that claim.

Repeated narrations, partial wordings in one place and fuller forms in another, the same chain and matn reappearing in a different context with a different legal weight—none of this is accidental once one reads Bukhārī through his eyes. He followed these patterns so closely that he later catalogued, in a separate treatise now included in al-Yawāqīt al-Ghāliya, those places where Imām al-Bukhārī repeats a ḥadīth with essentially the same isnād and text yet uses it to illuminate distinct questions in different parts of the work. For him, repetition was evidence of design, not forgetfulness.

For students this perspective is both unsettling and liberating. One is not entitled to say “Bukhārī proves X” until one can show how Bukhārī himself deploys a report across the architecture of his book and what that deployment implies in law and meaning. To lift a single occurrence, strip it of its heading, ignore its pairings and its echoes, and then parade it as “the ḥadīth on this issue” is not reading Bukhārī; it is conscripting Bukhārī into one’s own argument.

None of this dispenses with the technical work around isnād. That work was always there: routes of transmission traced and compared, narrators weighed, corroborating chains mapped, tensions between parallel narrations explored and, where necessary, left honestly unresolved, and the path by which a text travelled into fiqh and practice patiently followed. But for him, declaring that a report is ṣaḥīḥ was the beginning of the conversation, not its end. Once authenticity had been established, another set of questions had to be faced: what is this report doing here, in this place, under this heading; is it decisive in this context or supportive; is it closing a question or opening one; why does this chapter receive a partial wording while a fuller form appears elsewhere; and what happens to our earlier reading when the same wording re-emerges in a different section of the book?

To refuse such questions is to treat authenticity as a talisman. To ask them is to accept responsibility for what the compiler is actually doing on the page.

Madhāhib, Tarjīh, and the Price of a View

Read in this manner, the supposed contrast between “following a madhhab” and “following the ḥadīth” proves far less sharp than much contemporary rhetoric suggests. For Shaykh Yūnus, the legal schools were not alternatives to the ḥadīth corpus, but cumulative records of how generations of scholars had wrestled with, and organised, those very reports.

He treated the madhāhib as archives of serious reading: the early Ḥanafī deliberations, classical Mālikī practice, Shāfiʿī reasoning, the layered testimony of the Ḥanbalī tradition, and the voices of figures such as al-Awzāʿī, Sufyān al-Thawrī, Layth ibn Saʿd and Abū Thawr, who disturb our neat diagrams. These were not tribal banners under which to fight; they were records of how responsible minds grappled with the same texts in different times and places.

At the same time, he never allowed affiliation to do the work that only evidence can do. Before pronouncing on an issue, he would make his operative principles clear: what counts as decisive proof in that question, what counts as strong support, how long-established practice (ʿamal) is to be weighed, and how apparently competing texts are to be reconciled. Only then would he apply those principles, even when the conclusion cut across entrenched habit.

This is the soil from which several positions often associated with his name emerge: raising the hands at rukūʿ and on rising from it, the recitation of Sūrat al-Fātiḥah by the follower in silent prayers, the audibility of the basmalah, a preference for the shorter ifrād form of the iqāmah, a more generous allowance for wiping over ordinary socks, and the view—based on explicit textual evidence—that eating camel meat requires a fresh wuḍūʾ. Each of these can be turned, in the wrong hands, into a slogan about “breaking with X” or “standing for ḥadīth”. That was never his way.

What he modelled instead was tarjīḥ—preference between evidences—as a moral act. To prefer one view over another is not simply to announce a taste. It is to disclose one’s chain of reasoning, to admit the criteria one is using, and to carry the devotional cost of what one is saying. A ruling that in practice leads people to miss an obligatory prayer cannot be baptised as “piety”. Severity for its own sake is not waraʿ, and ease for its own sake is not raḥmah. Proportion is learnt when evidences are read with the compiler’s hand still visible.

For that reason he would often insist, sometimes explicitly and sometimes simply through the shape of a conversation, that one must “price” one’s conclusions. One cannot advocate an especially strict view in public and then wash one’s hands of what happens when ordinary worshippers try to live by it; nor can one promote a lax position and ignore the erosion of obligations that follows. A legal answer has consequences in the worship, contracts and family lives of real people. Honesty requires that those consequences be acknowledged. It was in this spirit that, on a now familiar journey between Madīnah and Makkah, he combined prayers on the road in a way clearly allowed by the texts. Some companions, preferring a harsher course, did not. They arrived having missed ʿAṣr altogether. His quiet comment afterwards—that a piety which ends in disobedience has been misnamed—carried more weight than any polemic.

Devotional Restraint and Filial Conversation with the Tradition

The same discipline governed his treatment of widely-practised devotions. On recurring questions such as fasting specifically on the fifteenth of Shaʿbān, or additional phrases that have become attached to popular supplications, his method was steady. He would first map the early juristic record across schools. He would then sift, line by line, the ḥadīth corpus that had been invoked in support. He distinguished between broad, well-attested encouragements—such as frequent fasting in Shaʿbān—and much narrower claims, such as singling out one particular date as having a distinct status with its own independent proofs. The result was usually a balanced conclusion that preserved genuine Sunnah practice, recognised the spiritual value of more general devotions, and declined only those specific attributions that the transmitted record could not honestly bear. In all this, the thread was the same: the religion does not need to be decorated; it needs to be protected.

His relationship with the commentarial tradition reflects the same combination of reverence and independence. He regarded Fatḥ al-Bārī as unmatched among the commentaries of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, and his admiration for Ibn Ḥajar was unambiguous. But respect did not mean paralysis. Where he felt that the internal logic of a chapter had not been drawn out fully; where a familiar attribution lacked a firm early basis; or where the placement of a report suggested an editorial intention that the standard commentaries left implicit, he did not hesitate to say so—gently, proportionately, and with adab. The notes now gathered under titles such as Nibrās al-Sārī ilā Riyāḍ al-Bukhārī and al-Fayḍ al-Jārī are written in this key: deferential in tone, real in engagement. They teach a posture before the tradition that is neither mute repetition nor cheap contradiction, but something closer to a filial conversation.

A Workflow and a Temperament

For those of us who now teach or write, his legacy can be translated into very practical habits. He would begin, as far as circumstances allowed, from the primary sources themselves rather than their later summaries. He took chapter headings seriously, treating them as compressed arguments that required unfolding. He read the reports under each heading more than once: first for the wording itself, and then again to understand the role each report played inside the chapter. He paid close attention to partial and complete wordings, to repeated narrations and shifting contexts, and allowed those patterns to guide his sense of the compiler’s intention.

He traced the earliest juristic discussions he could reach before leaning on later digests, and when he preferred one reading over another he wrote down his reasons and tried to be explicit about what that advice would cost in the practice of real worshippers. Where the evidence was genuinely ambiguous or insufficient, he resisted the urge to force a neat answer simply for the comfort of closure. He would rather leave a question open than stabilise it on ground he believed to be weak.

Alongside this workflow sat a particular temperament. He was wary of mistaking loudness for clarity or performance for honesty. Even when disagreement was sharp, his tone rarely was. He disliked arguments that tried to borrow certainty by attaching themselves to great names without demonstrating that those names really supported the position being claimed. He was protective of the language of the Prophet ﷺ, resisting its expansion to accommodate what our expectations would like him to have said. And he never forgot that legal and theological discussions spill into lived realities: the state of a person’s ṣalāh or zakāh or marital contract is not a debating point; it is part of what they will carry into the grave.

Style, for him, belonged to this same moral world. The way we write is part of how we train people to think. He read slowly and thought in lines that were long but never aimless. He preferred prose that carried argument rather than applause. In an age hungry for “bullet-point takeaways”, there is certainly a place for distillation, especially in teaching. Yet if we only ever offer conclusions detached from the path that produced them, we train impatience and reward superficiality. One of the quieter lessons I took from his majālis was that good prose should move at the speed of honest thought: clear, unhurried, unwilling to slice serious questions into slogans.

Scholarship as a Moral Trust

If we gather these strands together—the ethics of attribution, the insistence on reading Bukhārī as a constructed whole, the treatment of the madhāhib as archives rather than banners, the understanding of tarjīḥ as a priced moral commitment, the careful restraint around devotional practice, and the calm, serious engagement with commentary—a picture emerges that is very different from the way scholarly lives are often narrated.

His legacy is not, at its heart, a list of “strong views”, nor simply the fact that he taught Bukhārī for decades, nor even the memorable stories of spiritual states that naturally cluster around a life of such devotion. Those all have their place. What matters more—and what is easiest to lose in hurried tribute—is that he insisted, by example, that scholarly work has a moral register.

To cite a ḥadīth is to accept responsibility for the words one places on one’s tongue. To invoke Imām al-Bukhārī is to accept responsibility for reading him as an author rather than using his name as an ornament. To issue a ruling is to accept responsibility for the shape of other people’s prayers, fasts and contracts after they act upon it. To transmit devotional formulas is to accept responsibility for whether one has, even inadvertently, placed something at the level of the Prophet’s ﷺ speech that does not belong there.

If that sense of answerability is lost, even technically correct conclusions can become spiritually harmful. If, on the other hand, we allow this discipline to shape the way we read, teach and write, then works such as Nibrās, al-Fayḍ and al-Yawāqīt become more than useful references. They become an apprenticeship in how to think.

The biographical study you are about to read will, in shā’ Allāh, furnish the detail: the journeys, the teachers, the testimonies, the editorial history of his notes, the glimpses of private character that only students can provide. This introduction is intended as a companion of another sort. It is an invitation to approach those works, and the ḥadīth corpus more broadly, under a kind of quiet oath: that we will treat attribution as trust; that we will read Bukhārī as a book with a mind; that we will “price” our conclusions; and that we will prefer the slow dignity of evidence to the quick thrill of slogans.

If even a handful of readers leave with a steadier eye for chapter-logic, a cleaner habit of verification, and a quieter tongue in controversy, then something of what he embodied in his majālis will, by Allah’s permission, have been carried forward—not merely as story, but as practice.

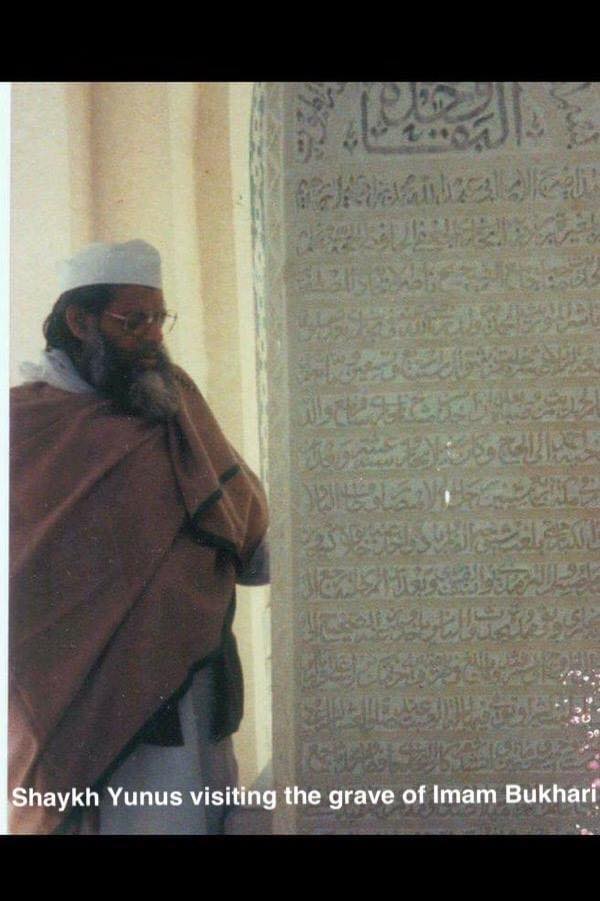

In the years since his passing, I have travelled to India several times. On a recent visit to Saharanpur, I was able to visit his grave and also to see the small room in Maẓāhir ʿUlūm where he lived for so many years. That modest space has now been carefully reorganised as a dedicated library of his own books and papers, with his annotated volumes and handwritten notes preserved and displayed. It was deeply moving to see how the place that once housed his daily labour in ḥadīth has itself become part of his ongoing legacy for students and visitors.

Grave inscription of Shaykh Muḥammad Yunus Jaunpuri

As with all translations, the views expressed in this work remain those of the author; my task has been to convey them with as much care and fidelity as I can. This project has been underway for some time, and I have translated the book in its entirety so that readers may engage it as a whole. While I do not necessarily share every conclusion that any author reaches, this edition is offered in a spirit of clarity, accuracy and scholarly service.

It is my sincere hope that this translation will offer a rich and illuminating experience to all who engage with it, and that it will deepen our understanding and appreciation of the intellectual and spiritual legacy it describes. I continue to share reflections on Shaykh Muḥammad Yūnus and related scholarly themes on hnadwi.com, where readers will find further essays and ongoing projects connected to this work.

If you notice any mistakes or have suggestions for improvement, I would be grateful if you could send them to huzaifahnadwi@gmail.com, so that any necessary corrections can be incorporated into future editions.

May Allah grant us the wisdom to traverse this ocean of knowledge with humility and sincerity, and may He bestow His peace and blessings upon His noble Messenger ﷺ, his family, and all his companions.